Tinkering with skies, clouds and oceans is risky, but maybe less risky than global warming

Some of it sounds like mad science, maybe the master plan of a Bond villain. One idea resembles a plot from The Simpsons.

Humans have given it a low-key name: geoengineering. But it's nothing less than changing the Earth — the air, the clouds, the oceans — so that we can hold off on global warming's most devastating effects until we cut our carbon pollution.

"Make no mistake: This is a really big deal," Daniel Schrag, director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment, told CBC Radio's The Current, specifically referring to solar geoengineering. "We're talking about engineering the climate intentionally for the whole planet."

Here are some of the big ideas that have been discussed, how they work and what they might mean for the planet.

Block the sun

This is The Simpsons one, though the proposal isn't to block the sun entirely like the evil Mr. Burns did in one popular episode.

Instead, picture this: Customized aircraft soar into the stratosphere, 20 kilometres or so, well above commercial aircraft, and spray tiny particles of sulphur or some other substance into the air — tens of thousands of tonnes, just to start. Then keep doing that for decades.

The particles would reflect sunlight and dim the sun by about one or two per cent, Schrag said.

That's a small enough change that we wouldn't likely notice on a day-to-day basis, but it would have a big impact.

For one thing, it's expected that it would work relatively quickly. A report released by the White House in June said it "offers the possibility of cooling the planet significantly on a timescale of a few years."

The report neither endorses nor rejects the approach — only saying that more research would make sense.

The risks are many, including changes to rain patterns, UV levels, animal life cycles and vegetation growth, as well as a big temperature spike if the process were suddenly stopped.

There are at least two big questions with this plan: if the world moves ahead with this technology, will people stop trying to reduce carbon emissions? And, with a technology that will change some countries more than others, who gets to control an entire planet's thermostat?

"Doing this sounds like a terrible idea, and it may be a terrible idea — except for the alternative, which is that we're going to let the Earth roast," Schrag said.

Make the clouds brighter

Let's say we decide against sending a squadron of planes to seed the sky with sulphur. How about a fleet of ships to brighten the clouds instead?

Sarah Doherty, a senior research scientist with the University of Washington's department of atmospheric sciences in Seattle, has found that the more low cloud cover we have, the cooler our planet. She's been researching how we might brighten clouds over the oceans by using sea salt to enrich marine clouds, as was detailed in a recent documentary on The Nature of Things, Apocalypse Plan B.

It's called marine cloud brightening.

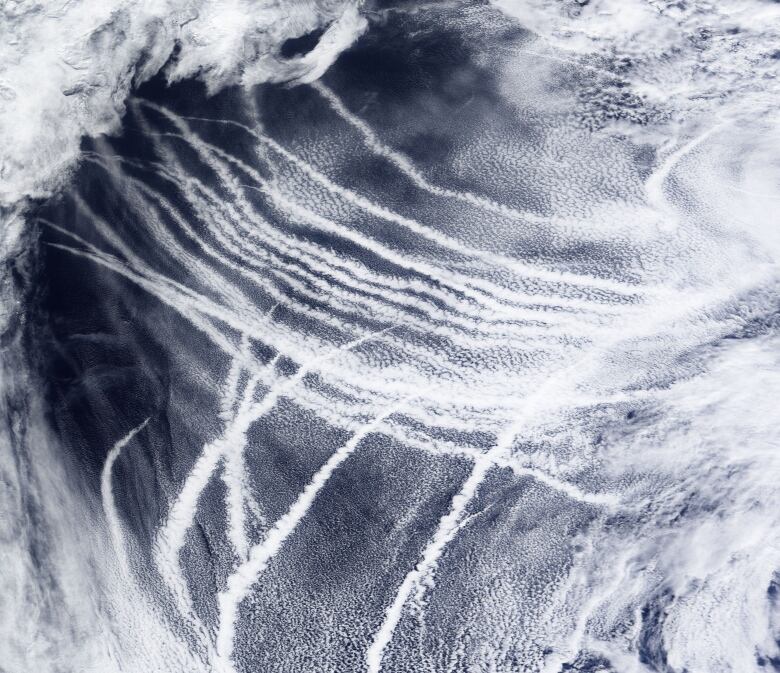

Some cargo ships already do this unintentionally, leaving "tracks" in the sky from their smoke stacks. The idea is to replicate that using sea salt instead of pollution.

But to brighten clouds on a large scale would take a lot of ships to make an impact.

"We would end up with something like 10,000 ships producing spray over broad regions," Doherty said.

She envisions an autonomous fleet that would run on renewable energy and respond to weather conditions in three ocean areas that tend to have lots of clouds: west of North America, west of South America and west of Africa.

But it has issues that are similar to dimming the sun: Doherty wants to know how changing the climate on such a large scale might affect circulation and rainfall patterns, perhaps causing droughts and floods.

Cover the Arctic with glass

This is another reflective proposal: make Earth's Arctic ice whiter by coating it with small glass beads.

The Arctic Ice Project has been working for about 15 years to try to protect the Arctic ice, which already acts as a huge reflector of the sun's rays. But the ice cap is caught in a feedback loop: The Earth warms and the ice cap shrinks, which lead to less reflecting and more warming, and so on.

The engineers behind the project have shown that the beads work on a small scale on lakes in North America and hope it can be done on large swaths of ice off Greenland.

The super-reflective beads are designed to be as unobtrusive to the local ecosystem as possible, but questions remain about unintended side-effects and who would foot a multibillion-dollar bill for such a project.

Jordan Payne, a spokesperson for the group, told CBC News this week that they've partnered with other groups for more research, focusing on safety and efficacy. They hope to publish some new white papers and research publications this year.

"We've observed a growing recognition of the urgency of climate action as extreme weather events occur," she said.

Hoovering up the carbon (and a few other things)

There are two basic kinds of climate manipulation.

The first is to reflect or block sunlight, such as in the examples above, as well as in other proposals both big (mirrors in space!) and small (making paint as white as possible).

The second is to try to remove as much carbon dioxide as possible out of the atmosphere.

That could be growing a huge number of trees, throwing iron in the ocean to promote plankton growth or sucking carbon dioxide straight out of the air.

Anna-Maria Hubert, an international environmental law expert at the University of Calgary, said carbon capture is further down the road than solar geoengineering. She expects more pilot-scale projects to ramp up over the next five years or so.

The U.S. government, for example, has offered $3.5 billion US in grants to companies that will capture and permanently store carbon dioxide using "direct air capture," where chemical reactions remove carbon dioxide from the air to be stored underground or used, for instance, to make concrete or aviation fuel.

That's partly because carbon capture tends to be more local and partly because taking carbon from the atmosphere will be necessary to keep global warming no more than 2 C above the pre-industrial average.

"The ambitious timeline would be like the end of this decade, or next decade, but I think most people … include a significant role for carbon dioxide removal to stay below two degrees. So that's creating the policy imperative," Hubert said.

Some of the grander ideas may be decades away.

"In 20, 30, 40 years, there's going to be enough climate warming and climate disruption occurring that people will think about using these mechanisms to cool climate," said Doherty of the University of Washington.

"I'd rather they were able to make an informed decision than an uninformed decision, because I think they're going to think about these options anyway regardless of how much information they have. That cat's kind of out of the bag."

*****

Credit belongs to : www.cbc.ca

MaharlikaNews | Canada Leading Online Filipino Newspaper Portal The No. 1 most engaged information website for Filipino – Canadian in Canada. MaharlikaNews.com received almost a quarter a million visitors in 2020.

MaharlikaNews | Canada Leading Online Filipino Newspaper Portal The No. 1 most engaged information website for Filipino – Canadian in Canada. MaharlikaNews.com received almost a quarter a million visitors in 2020.